The changing climate will challenge Nordic forests; our own actions will define just how hard

As Central and Eastern Europe’s forestry sectors are recovering from unprecedented spruce bark beetle damages, the Nordic countries are paying attention to the lessons of a changing climate. Given the rate at which the Nordic climate has warmed (and continues to warm), adaptation processes must be accelerated.

Beetles on the Rise

There is nothing new about an insect such as the spruce bark beetle, Ips typographus, killing a tree. This is normal, even far north in Finland. In the past, we typically saw damage only after a major storm had created ample amounts of easy breeding material for the beetles (wind-felled trees). Leveraged by this, populations of these aggressive bugs grew to the point where they were also able to attack and kill healthy standing trees, until the status quo returned.

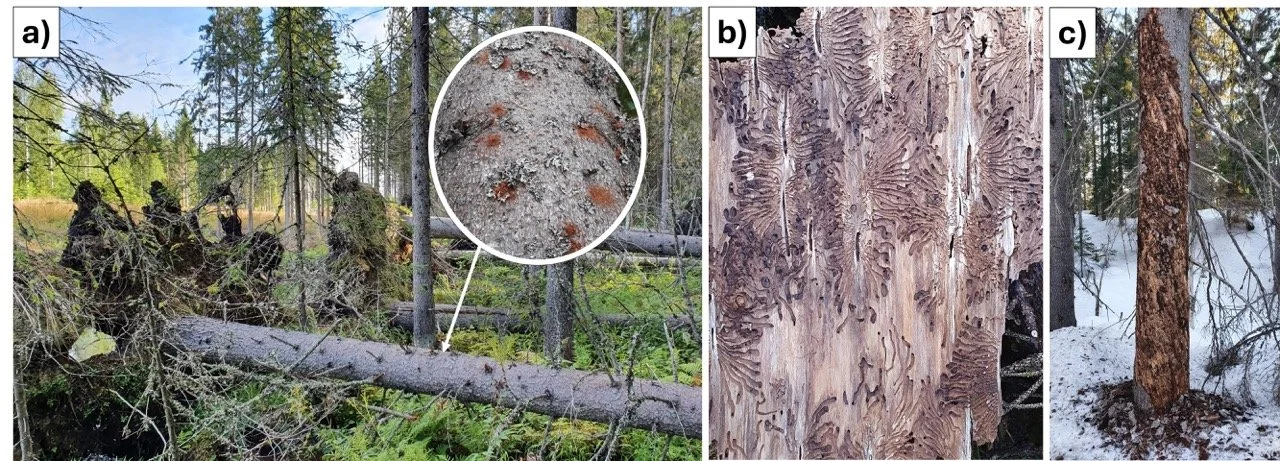

Anatomy of a typical spruce bark beetle damage event in Finland: wind has felled trees that have been attacked by the beetles. a) The brown dust piles in the zoomed image show where beetles penetrated the bark; b) the beetles breed and reproduce under the bark, in the tree phloem, leaving their signature galleries on the trunk and the bark; c) where beetle numbers are high enough, they are also able to attack standing trees, causing localised tree mortality. Photo credit: Markus Melin, Luke.

In the past decade, the balance has been upset by intense drought and heat spells which, via drought stress, make spruce forests especially susceptible to beetles. Where an episode like a storm is a localised event, however, massive droughts can weaken and expose an entire forest landscape. Meanwhile, the beetle benefits: she can grow from larvae to adult faster and thereby reproduce more than once during the growing season. The outcome, as we are seeing, is beetle damage at unprecedented scales across Central and Eastern Europe.

Small scale bark beetle outbreak at the edge between a clear-cut and mature forest in southwest Finland. In the worst regions of Central and Eastern Europe, these types of landscapes are more common than healthy forests. Photo credit: Markus Melin, Luke.

The Role of Forest Composition

When forest damage occurs at unusually large scales, it can be easy to assume the climate is to blame. Recently, however, a compelling body of research from Central Europe has shown that an equally important variable in explaining such widespread damage was the amount of spruce in the landscape [1, 2, 3, 4]. This was especially true where spruce was planted outside its native range on sites it was not adapted to and where it, therefore, stood no chance against the beetles when the drought hit. Spruce was favoured as it provides high-quality timber, but nobody could predict the scale and intensity of the droughts, the heat and the beetles, and the subsequent damage to entire spruce landscapes. Regardless of climate, landscape-scale forest damages do not occur without the enabling condition of a landscape of vulnerable trees. Here, the crucial lesson for us in the Nordics is to avoid creating that landscape.

Designing Climate-Resilient Forests

This is a core task within Precilience; to demonstrate the types of forests most susceptible to climate-exacerbated damage agents such as the spruce bark beetle. This is especially crucial for adaptation: the forests we regenerate today should still grow for 60-80 years, even in a more disruptive climate. So far, southern Finland has seen a period of “sprucification” — including on sites not optimal for the spruce — that is not slowing down. Colleagues in Central Europe have valid stories to tell about the future of such forests. Our aim is to translate what they mean in reality for forest owners, practitioners and decision makers. The coming decades are when we can and should steer the future of Nordic forestry into a less damage-prone direction, or else we risk learning the hard way.

Written by Markus Melin, Research Scientist and Research Manager, Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Forest Health and Biodiversity Group.